In 1834, colonists received titles to their lands and the Refugio Municipality was established. Five and a quarter leagues (23,247 acres) was granted to Joshua Davis; this land was on the west side of the Guadalupe River and spanned the distance from the confluence to the site of Mesquite Landing and slightly south. He died intestate in 1835 and the disposition of those five and a quarter leagues was in legal dispute until the late 1800s. Early colonists in this area were Nicholas Fagan, Edward Perry, John B. and Anthony Sideck, Peter Teal — along with the Captains Valdez and Hernandez. They formed an informal and unofficial colony of their own — a colony that would mostly negate politics, heritage or religious persuasion for many years to come.

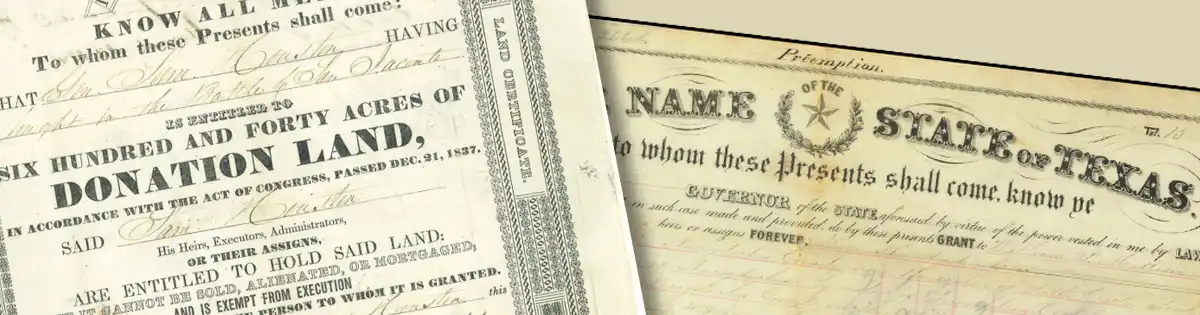

The Revolution in 1836 gave rise to more means for citizens or prospective citizens of the new Republic of Texas to acquire land. As mentioned, land from the confluence to Mesquite Landing (West of the Guadalupe) was all granted to Joshua Davis; he did not live long on the land and died without heirs who were legal residents of the Republic. What legally happened to the title immediately is unclear in the old records, but ultimately George C. Hatch was given a certificate for Abstract 166 in the Refugio District and Pierce Rollins was named on Abstract 358 next to it. [Note: The term abstract refers to an original land survey describing an area transferred from the public domain by either the Republic of Texas or the State of Texas.] These two abstracts straddle the site of Mesquite Landing and were classified as riparian land, bordering a flowing water source.

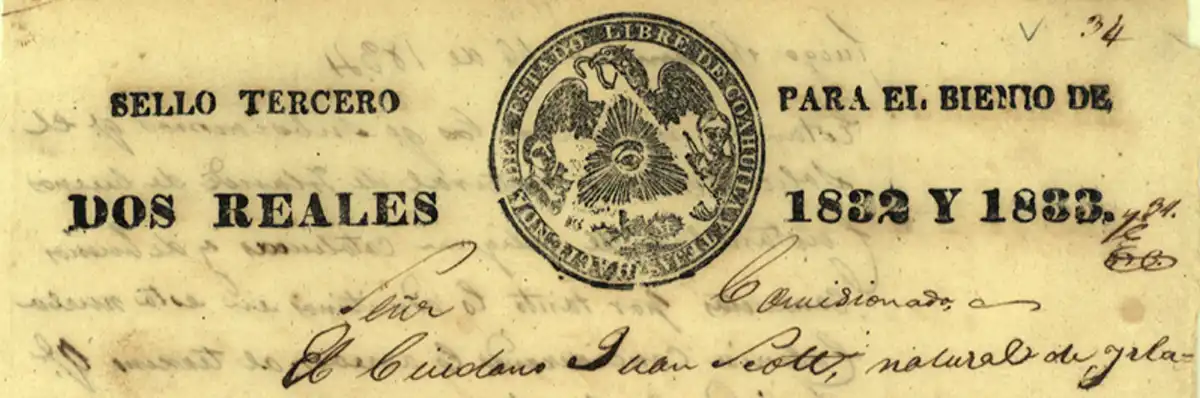

During the period of the Republic, there was a general clamoring of the people to secure lands for private use. There had been Spanish land grants through empresario contracts, and grants made to Mexican ranchers who were native Tejanos. The Republic made Headright Grants based on special conditions met per the Constitution of 1836. There were Preemption Grants for those who had settled on unclaimed public property and improved it. Later there were Homestead Grants. Bounty and Donation Grants were given based on military service. Vast areas of Texas lands were also granted in return for making improvements, such as building canals, digging irrigation ditches, constructing shipbuilding facilities or clearing river channels.

Acquiring land in Texas, barring a simple sale, was a highly complicated system. And it was fairly loosely controlled in some areas. Land may have been granted to people who never showed up to live on it, as in the case of the area at Mesquite Landing. Local ranchers did not have fenced lands, so livestock of neighbors mingled and grazed together. Hunters found game where they might. Travelers crossed rivers and streams where it was most convenient. This creates a challenge for those who would accurately tell the history of a region or significant place. Various accounts published in the Addenda tell, through court records, of the struggle to claim this little spot of real estate through the years.

Those who actually laid a legal claim to the land at Mesquite Landing may have built homes and occupied the site with their families — or not. But the fact remains, that the historic landing would likely have been a busy place, with all manner of sea-going crafts bringing people and goods up the Guadalupe River from ports along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. And down the river again from Victoria and the big ranchos that lined the waterways.

Go to: Statehood